BBC Perceptible Investigations, el-Geneina

Hafiza

Hafiza“She left no last words. She was dead when she was carried away,” says Hafiza quietly, as she describes how her mom was once killed in a town beneath siege in Darfur, all the way through Sudan’s civil struggle, which started precisely two years in the past.

The 21-year-old recorded how her community’s while was once became the other way up by way of her mom’s demise, on one in all a number of telephones the BBC Global Carrier controlled to get to population trapped within the crossfire in el-Fasher.

Below consistent bombardment, el-Fasher has been in large part trim off from the out of doors international for a 12 months, making it unimaginable for reporters to go into town. For protection causes, we’re handiest the use of the primary names of population who sought after to movie their lives and proportion their tales at the BBC telephones.

Hafiza describes how she abruptly discovered herself liable for her five-year-old brother and two yongster sisters.

Their father had died earlier than the beginning of the struggle, which has pitted the military in opposition to the paramilitary Fast Aid Forces (RSF) and led to the arena’s greatest humanitarian extremity.

Hafiza

HafizaThe 2 competitors were allies – coming to energy in combination in a coup – however fell out over an across the world sponsored plan to walk against civilian rule.

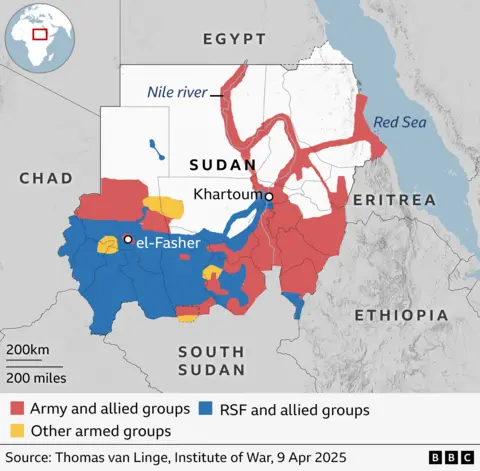

Hafiza’s house is the ultimate main town managed by way of the army in Sudan’s western patch of Darfur, and has been beneath siege by way of the RSF for the while 365 days.

In August 2024, a shell clash the marketplace the place her mom had long past to promote family items.

“Grief is very difficult, I still can’t bring myself to visit her workplace,” says Hafiza in one in all her first video messages then receiving her telephone, in a while then her mom’s demise.

“I spend my time crying alone at home.”

Each side within the struggle had been accused of struggle crimes and intentionally concentrated on civilians – which they abjure. The RSF has additionally in the past denied accusations from the USA and human rights teams that it has dedicated a genocide in opposition to non-Arab teams in alternative portions of Darfur then it seized keep watch over of the ones subjects.

The RSF controls passage out and in town and once in a while permits civilians to let go, so Hafiza controlled to ship her siblings to stick with community in a impartial section.

However she stayed to struggle to earn cash to help them.

In her messages, she describes her days distributing blankets and H2O to displaced population dwelling in shelters, serving to at a public kitchen and supporting a breast most cancers consciousness crew in go back for a negligible cash to backup her live to tell the tale.

Her nights are spent abandoned.

“I remember the places where my mother and siblings used to sit, I feel broken,” she provides.

In nearly each and every video 32-year-old Mostafa despatched us, the pitch of shelling and gunfire may also be heard within the background.

“We endure relentless artillery shelling, both day and night, by the RSF,” he says.

One occasion, then visiting community, he returned to seek out his space related town centre were clash by way of shells – the roof and partitions had been broken – and looters had ransacked what was once left.

“Everything was turned upside down. Most houses in our neighbourhood have been looted,” he says, blaming the RSF.

Hour Mostafa was once volunteering at a refuge for displaced population, the section got here beneath intense assault. He stored his digicam rolling as he concealed, flinching at every explosion.

“There is no safe place in el-Fasher,” he says. “Even refugee camps are being bombed with artillery shells.

“Loss of life can hit somebody, anytime, with out ultimatum… by way of a bullet, shelling, starvation or crave.”

In another message, he talks about the lack of clean water, describing how people drink from sources contaminated with sewage.

Both Mostafa and 26-year-old Manahel, who also received a BBC phone, volunteered at community kitchens funded by donations from Sudanese people living elsewhere.

The UN has warned of famine in the city, something that has already happened at the nearby Zamzam camp, which is home to more than 500,000 displaced people.

Many people cannot get to the market “and in the event that they journey, they to find top costs”, explains Manahel.

“Each and every community is equivalent now – there is not any affluent prosperous or penniless. Population can’t find the money for the unsophisticated prerequisites like meals.”

Manahel

ManahelAfter cooking meals such as rice and stew, they deliver the food to people in shelters. For many, it is the only meal they will have for the day.

When the war started, Manahel had just finished university, where she studied Sharia and law.

As the fighting reached el-Fasher, she moved with her mother and six siblings to a safer area, further away from the front line.

“You lose your house, the whole lot you personal and to find your self in a unused park with not anything,” she says.

But her father refused to leave their house. Some neighbours had entrusted him with their belongings, and he decided to stay to protect them – a decision that cost him his life.

She says he was killed by RSF artillery in September 2024.

Manahel

ManahelSince the siege began a year ago, almost 2,000 people have been killed or injured in el-Fasher, according to the UN.

After sunset, people rarely leave their homes. The lack of electricity can make night-time frightening for many of el-Fasher’s one million residents.

People with solar power or batteries are scared to turn lights on because they “might be detected by way of drones”, explains Manahel.

There were times we could not reach her or the others for several days because they had no internet access.

But above all these worries, there is one particular fear that both Manahel and Hafiza share if the city falls to the RSF.

“As a lady, I would possibly get raped,” Hafiza says in one of her messages.

She, Manahel and Mostafa are all from non-Arabic communities and their fear stems from what happened in other cities that the RSF has taken, most notably el-Geneina, 250 miles (400km) west of el-Fasher.

In 2023 it witnessed horrific massacres, along ethnic lines, which the US and others say amounted to genocide. RSF fighters and allied Arab militia allegedly targeted people from non-Arab ethnic groups, such as the Massalit – which the RSF has previously denied.

A Massalit woman I met in a refugee camp over the border in Chad described how she was gang-raped by RSF fighters and was unable to walk for nearly two weeks, while the UN has said girls as young as 14 were raped.

One man told me how he witnessed a massacre by RSF forces – he escaped after he was injured and left for dead.

The UN estimates that between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed in el-Geneina alone in 2023. And now more than a quarter of a million people from the city – half its former population – are among those living in refugee camps in Chad.

We put these accusations to the RSF but it did not respond. However, in the past it has denied any involvement in ethnic cleansing in Darfur, saying the perpetrators had worn RSF clothing to shift the blame to them.

Few reporters have had access to el-Geneina since then, but after months of negotiation with the city’s civil authorities, a BBC team was allowed to visit in December 2024.

We were assigned minders from the governor’s office and were only allowed to see what they wanted to show us.

It was immediately clear that the RSF was in control. I saw their fighters patrolling the streets in armed vehicles and had a brief conversation with some of them, when they showed me their anti-vehicle rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launcher.

It did not take long to realise how differently they viewed the conflict. Their commander insisted there were no civilians like Hafiza, Mostafa and Manahel living in el-Fasher.

“The one who remains in a struggle zone is taking part within the struggle, there are not any civilians, they’re all from the military,” he said.

He claimed el-Geneina was now peaceful and that most of its residents – “round 90%” – had come back. “Properties that had been in the past unfilled are actually i’m busy once more.”

But hundreds of thousands of the city’s residents are still living as refugees in Chad, and I saw many deserted and destroyed neighbourhoods as we drove around.

With the minders watching us, it was hard to get a true picture of life in el-Geneina. They took us to a bustling vegetable market, where I asked people about their lives.

Each time I asked someone a question, I noticed them glance at the minder over my shoulder before answering that everything was “high-quality”, apart from a few comments about high prices.

However, my minder would often whisper in my ear afterwards, saying people were exaggerating about the prices.

We ended our trip with an interview with Tijani Karshoum, the governor of West Darfur whose predecessor was killed in May 2023 after accusing the RSF of committing genocide.

It was his first interview since 2023, and he maintained he was a neutral civilian during the el-Geneina unrest and did not side with anyone.

“We’ve became a unused web page with the slogan of relief, coexistence, transferring past the bitterness of the while,” he said, adding that the UN’s casualty figures were “exaggerated”.

Also in the room was a man who we understood to be a representative of the RSF.

Karshoum’s answers to nearly all my questions were almost identical, whether I was asking about accusations of ethnic cleansing or about what happened to the former governor, Khamis Abakar.

Nearly two weeks after I spoke to Karshoum, the European Union imposed sanctions on him, saying he “holds accountability within the horrendous assault” on his predecessor and that he had “been considering making plans, directing or committing… severe human rights abuses and violations of global humanitarian regulation, together with killings, rape and alternative severe modes of sexual and gender-based violence, and grab”.

I followed up with him to get his response to these accusations, and he said: “Since I’m a suspect on this topic, I consider any observation from me would dearth credibility.”

However he mentioned that he “was once by no means a part of the tribal warfare and remained at house all the way through the clashes” and added that he was not involved in any violations of humanitarian law.

“Accusations of killings, abductions, or rape will have to be addressed via an separate investigation” with which he would co-operate, Karshoum said.

“From the beginning of the warfare in Khartoum, we driven for relief and proposed important tasks to forbid violence in our socially fragile shape,” he added.

Mostafa

MostafaGiven the stark contrast between the narrative promoted by those in control of el-Geneina and the countless stories I heard from refugees across the border, it is hard to imagine people ever returning home.

The same goes for 12 million other Sudanese people who have fled their homes and are either refugees abroad or living in camps inside Sudan.

In the end, Hafiza, Mostafa and Manahel found life in el-Fasher unbearable and in November 2024 all three left the city to stay in nearby towns.

With the military regaining control of the capital, Khartoum, in March, Darfur remains the last major region where the paramilitaries are still largely in control – and that has turned el-Fasher into an even more intense battlefield.

“El-Fasher has transform horrifying,” Manahel said as she packed her belongings.

“We’re retirement with out realizing our destiny. Do we ever go back to el-Fasher? When will this struggle finish? We don’t know what’s going to occur.”