Patrícia Pascal

Patrícia PascalWhen she was once a tender kid and taking too lengthy to get in a position for college, crowd get-togethers or to sing within the church choir, Cape Verdean musician Carmen Souza was once continuously instructed to “ariope”.

What she didn’t realise till years nearest was once that the Creole promise got here immediately from the English promise “hurry up”.

“We have so many words that derive from the British English,” Souza, a jazz singer-songwriter and instrumentalist, tells the BBC.

“‘Salong’ is ‘so long’, ‘fulespide’ is ‘full speed’, ‘streioei’ is ‘straightaway’, ‘bot’ is ‘boat’, and ‘ariope’ – which I always remember my father saying to me when he wanted me to pick up my pace.”

Ariope is now considered one of 8 songs that Souza has composed for the magazine Port’Inglês – which means English port – to discover the little-known historical past of the 120-year-old British presence in Cape Verde. It began off as analysis for her grasp’s level.

“Cape Verdeans are very connected to music – in fact, we always say that music is our biggest export – and so I wondered whether there was also a musical impact,” she says.

There are only a few recordings of compositions of the month – Souza did uncover that an American ethnomusicologist, Helen Heffron Roberts, recorded some within the Thirties however they’re on very fragile wax cylinders and will best be listened to in particular person at Yale College in america.

So in lieu than rearranging timeless recordings, Souza – and her musical spouse Theo Pas’cal – created unused song, impressed by way of tales she got here throughout.

She has blended jazz and English sea shanties with Cape Verdean rhythms – together with the funaná, performed on an iron rod with a knife and the accordion, and the batuque, performed by way of ladies and in keeping with African drumming rhythms.

Getty Photographs

Getty PhotographsThe Cape Verdean islands lie about 500km (310 miles) off the coast of West Africa. They’re most commonly arid, with restricted arable land and susceptible to drought.

However they’re a strategic halfway level within the Atlantic Ocean, and so they have been first managed by way of the Portuguese as they traded between south-east Asia, Europe and the Americas – in spices, silk and enslaved society. With the abolition of the slave industry, Cape Verde lost in decrease.

Cape Verde remained a Portuguese colony till 1975 – however all through the 18th and nineteenth Centuries, British traders settled and Cape Verde as soon as once more turned into a bustling crossroads.

The British got here for the inexpensive labour, goats, donkeys, salt, turtles, amber and archil, a distinct ink that was once impaired in British garments production.

They constructed roads, bridges and advanced the herbal ports – which turned into referred to as Port’Inglês – and arrange coaling stations, with coal introduced in from Wales.

São Vicente’s Mindelo port turned into an important refuelling restrain for steamships sporting items around the Atlantic Ocean or to Africa – and an impressive international communications hub with the 1875 arrival of a submarine cable station.

Souza’s exploration of the British presence in Cape Verde temporarily turned into private.

“As I started to research, I found so many personal connections,” Souza says – together with the truth that her grandfather loaded coal directly to ships in Mindelo.

That impressed her to jot down Ariope – the tale of an used guy urging a more youthful guy, who prefers to stick within the shadow taking part in his guitar, to “ariope”. The British ships are coming and the sailors don’t like to attend – “fulespide, streioei”, the music is going.

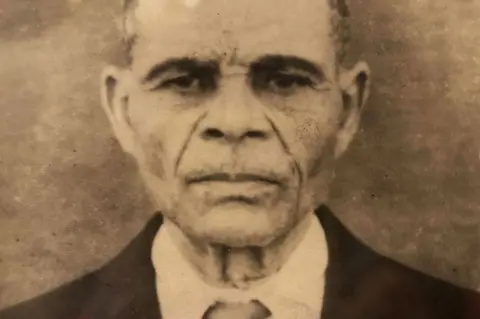

Carmen Souza’s crowd

Carmen Souza’s crowdSouza imagines the spirit of her grandfather within the music. He impaired to play games the mess around – and was once referred to as a splendid storyteller.

“I was told that if you had to walk with him for kilometres, you wouldn’t notice the distance because it would be one funny story after another.”

Souza is a part of Cape Verde’s immense diaspora. She was once born in Portugal, and now lives in London. In keeping with the Global Group for Migration (IOM), there are about 700,000 Cape Verdeans dwelling in a foreign country – two times as many as at house.

Traditionally, society have been pressured to go for paintings on account of famine, drought, poverty and rarity of alternatives.

This motion contributed to the islands’ deep, affluent prosperous custom of strongly unique song, together with the melancholic morna made well-known by way of singer Cesária Évora and declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by way of Unesco in 2019.

The composer in the back of lots of the songs that made Évora an international celebrity was once Francisco Beleza – sometimes called B Léza. He revolutionised morna and was once considered one of Cape Verde’s maximum influential writers, composers and morna singers.

In keeping with Souza’s analysis, he additionally regarded as the British presence to be extra advisable than the Portuguese – a minimum of to middle-class Cape Verdeans.

Souza’s monitor Amizadi, a mixture of funaná and jazz, was once impressed by way of B Léza’s wondershock of the British. He composed a morna – Hitler ca ta ganha guerra, ni nada, which means “Hitler will not win the war” to turn team spirit with the British society all through International Struggle II – or even raised cash for the British struggle struggle.

Souza discovered that ports have been “an important hub for musicians” who flocked there to be told the song – and tools – of visiting overseas sailors.

They combined them with Cape Verdean rhythms to form unused sounds. The mazurka – derived from a Polish musical method – and contradança from the British quadrille dance.

Early written data of Cape Verdean song are scarce – the Portuguese colonists didn’t report generation and family on Cape Verde alternative than data of taxes and commodities.

Additionally they forbidden the batuque – for being too loud and too African – and funaná as a result of its lyrics challenged social inequalities.

However Souza discovered an smart access within the diary of British naturalist Charles Darwin, who arrived in Cape Verde in 1832 – the primary restrain on his well-known Beagle voyage to review the dwelling international.

He describes an come across with a bunch of about 20 younger ladies who, writes Darwin, “sung with great energy a wild song, beating with their hands upon their legs”.

That, says Souza, is almost certainly an early efficiency of batuque – and he or she was once impressed to jot down the music Sant Jago by way of Darwin’s accounts of the nice and cozy hospitality he won on Cape Verde.

Many more youthful Cape Verdean musicians generally tend to not play games the islands’ used rhythms, and a few just like the contradança are slowly death out.

Souza hopes that her Port’Inglês magazine will encourage more youthful generations that “there is a way to do something new with the traditional genres”.

“I always bring some different elements – improvisation, the piano, the flute, the jazz harmonisation – so that the music is going through another process of creolisation.”

Port’Inglês by way of Carmen Souza is exempt via Galileo MC

Getty Photographs/BBC

Getty Photographs/BBC