BBC

BBCThe sister of a 16-year-old boy who drowned week swimming bare at a Christian sleep camp in Zimbabwe run through kid abuser John Smyth blames the Church of England for his loss of life.

“The Church knew about the abuses that John Smyth was doing. They should have stopped him. Had they stopped him, I think my brother [Guide Nyachuru] would still be alive,” Edith Nyachuru informed the BBC.

The British barrister had moved to Zimbabwe together with his spouse and 4 kids from Winchester in England in 1984 to paintings with an evangelistic organisation.

This was once two years nearest an investigation seen he had subjected boys in the United Kingdom, a lot of whom he had met at Christian sleep camps run through a treasure he chaired that was once related to the Church, to hectic bodily, mental and sexual abuse.

The 1982 file, ready through Anglican clergyman Mark Ruston, concerning the canings stated “the scale and severity of the practice was horrific”, with accounts of boys crushed so badly they bled, with one describing how he had to put on nappies till his wounds scabbed over.

In spite of those stunning revelations, basically involving boys from elite British people faculties, the Rushton file was once no longer extensively circulated.

A decade on, elderly 50, Smyth had established himself as a revered member of the Christian nation in Zimbabwe. He had arrange his personal organisation, Zambesi Ministries, with investment from the United Kingdom – and was once dispensing alike punishments at camps that he advertised on the nation’s lead faculties.

Ms Nyachuru says her brother’s travel were an early Christmas provide from considered one of his alternative sisters, who had picked up considered one of Smyth’s brochures and been inspired with all of the actions on trade in for the age.

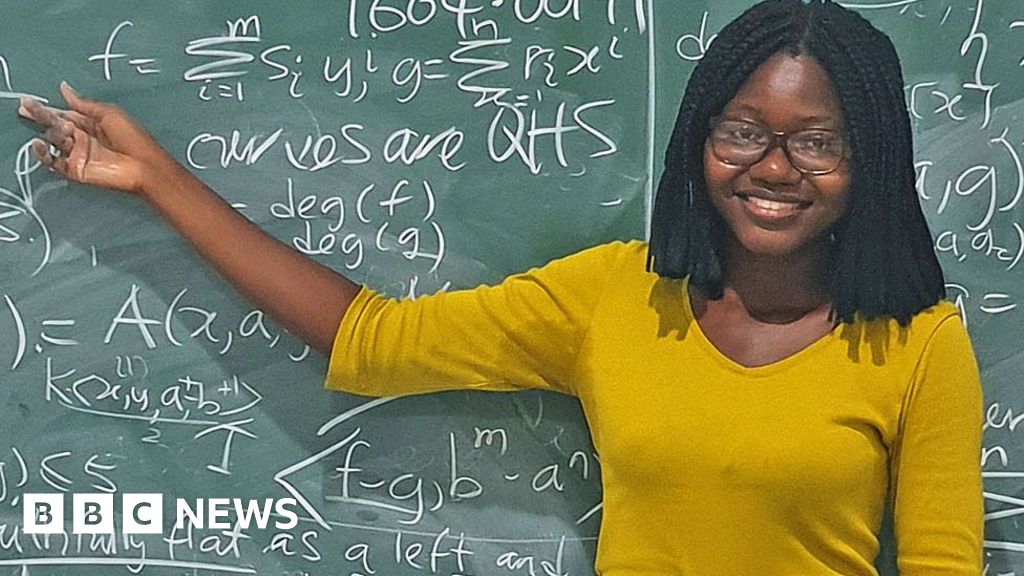

As she appears at an vintage {photograph} of Information, she says he was once the youngest of 8 siblings, and the one boy: “He was very loved by everyone.

“A nice-looking boy… Information was once because of be made head boy refer to 12 months,” she remembers, adding that he was “an clever boy, a excellent swimmer, sturdy, wholesome with out a recognized clinical situations”.

But within 12 hours of him being dropped at the camp at Ruzawi School in Marondera, 74km (46 miles) from the capital, Harare, on the evening of 15 December 1992, the family received a call to say he had died.

Witnesses say that like all the boys, Guide had gone swimming naked in a pool before bed – a camp tradition. The other boys returned to the dormitory, but Guide’s absence was not noticed – which his sister finds surprising – and his body was found at the bottom of the pool the next morning.

His family rushed to the mortuary but Ms Nyachuru’s shock was compounded by confusion when she was stopped by officers from viewing his body: “They informed me: ‘You’ll’t proceed in there as a result of he’s indecently dressed.’

“It was only my father, my brother-in-law and our pastor who went in and put him in the coffin.”

Nakedness seems to be one thing Smyth was once fixated on at his camps. Camp attendees have informed of the way he would frequently parade round with out garments within the boys’ dormitories – the place he additionally slept, in contrast to alternative body of workers participants.

He would additionally bathe bare with them within the communal showers and the lads have been ordered to not put on underpants in mattress.

“He promoted nakedness and encouraged the boys to walk around naked at the summer camp,” a former scholar who attended a camp at Ruzawi in 1991 informed the BBC.

However his jocular way put a lot of them at diversion, he stated.

“Smyth was very friendly, laid-back, approachable, he was really fun, always joking.

“Smyth would additionally move the dorms and bathe segment dressed in not anything however a towel slung over his shoulder.”

The reason given for the no-underwear-in-the-evening rule was “as a result of it could put together them develop”, he recalled.

Smyth gave talks on masturbation, would sometimes lead prayers in the nude and encouraged naked trampolining, an activity he described as “flappy leaping” – all behaviour noted in an investigation by Zimbabwean lawyer David Coltart that was launched in May 1993.

It was the thrashings that Smyth was giving boys with a notorious table tennis bat, dubbed “TTB”, that led a parent to the door of Coltart, who worked at a law practice in Zimbabwe’s second city, Bulawayo.

She wanted to know why one of her sons had returned from a holiday camp with bruises on his buttocks so severe that she took him to a doctor, who found a “12cm x 12cm bruise”.

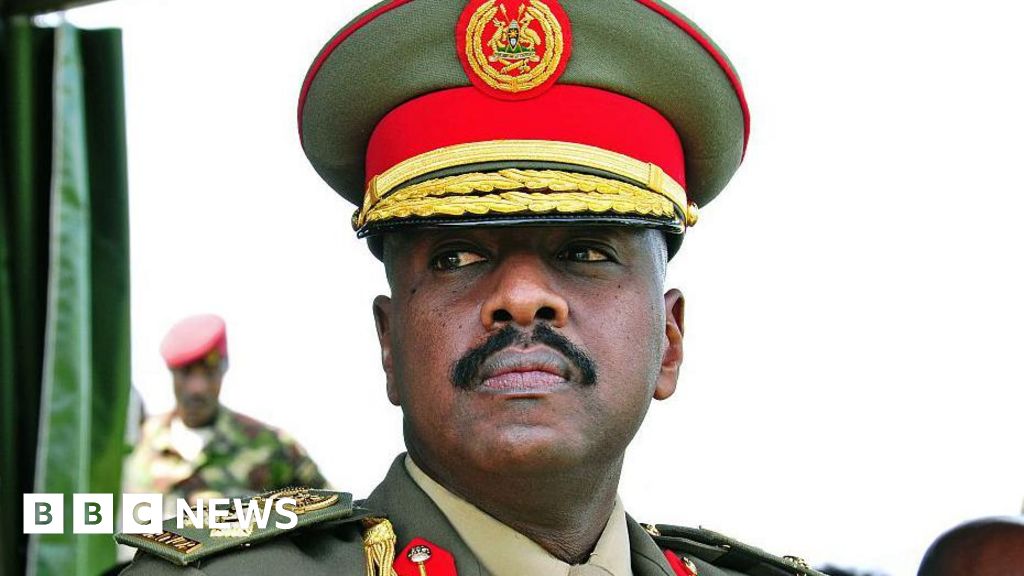

“She noticed those and demanded to understand what took place and next it got here out that her son were badly crushed within the nude, and he or she got here to me for recommendation,” Coltart, now mayor of Bulawayo, told the BBC.

“Once I heard that this was once a Christian organisation – I’m an elder within the Presbyterian Church – I were given keep of my pastor and we were given keep of the Baptist Church, Methodist Church and two alternative church buildings within the town and next I used to be recommended through the ones church buildings to research the subject,” he said.

Forty-four-year old Jason Leanders, who went on the camp that immediately followed Guide’s death, said he was beaten three to four times a day by Smyth, who would put his hands into his pants to check he had not put on extra layers to cushion his buttocks.

“My bum was once unlit,” he told the BBC. “However being a boy, you operate tricky.”

For many boarding school students, corporal punishment was regarded as “commonplace”, former Zimbabwean cricketer Henry Olonga, who was attending the camp the night Guide died, said in his 2015 autobiography.

But after Coltart managed to track down the Rushton report, the severity of the problem became apparent. He wrote to Smyth instructing him to immediately stop the Zambesi Ministries camps.

“It was once calculated, he concerned with boys. He groomed younger males. He inspired them to tug showers within the nude with him. There was once a trend of violence,” he said.

But Coltart’s dealings with Smyth proved difficult.

“He was once a extremely articulate guy and moderately competitive within the conferences that I had with him. He hired all his abilities as a barrister to hunt to intimidate. He was once used than me. I used to be next a somewhat younger attorney in my 30s. He exploited the truth that he was once an English QC [Queen’s Counsel].”

Rather than comply with Coltart’s various requests, he doubled down and in a letter to parents ahead of the August 1993 camps, described himself as “a father determine to the camp” and defended the nudity and corporal punishment, writing: “I by no means cane the lads, however I do whack with a desk tennis bat when essential… even supposing maximum regard TTB (as it’s affectionately recognized) as minute greater than a comic story.”

This time there appears to have been no cloaking of the beatings as “religious self-discipline” as had been the case in the UK. He also admitted to Coltart that he took photographs of naked boys, but said they were “from shoulders up” for publicity purposes.

Coltart contacted two psychologists with his findings, both of whom advised that Smyth should stop working with children.

His 21-page report was then published in October 1993, and circulated to head teachers and church leaders in Zimbabwe.

“The file was once by no means printed extensively, aware of the hazards of a defamation go well with,” Coltart said.

However it “mainly blocked him in his tracks in Zimbabwe” as the private schools were his harvesting ground, he said. Zambesi Ministries camps did continue in some guise, but not at schools or under Smyth’s leadership

Coltart then instructed another law firm to pursue a legal case against Smyth who was eventually charged with culpable homicide over Guide’s death, as well as charges relating to the beatings.

But, according to former BBC TV producer Andrew Graystone in his 2021 book about the abuse, the case was bedevilled with problems, police documents were missing and Smyth’s legal prowess led to the prosecutor being removed – another one was never appointed, so the case was essentially shelved in 1997.

Ms Nyachuru says no post-mortem was carried out at the time – Guide was buried on the day he drowned in the family’s home village, with Smyth presiding over the funeral.

Following the Coltart report, Smyth faced deportation from Zimbabwe but Graystone says he used his significant connections to avoid this, lobbying various cabinet ministers – some of whose sons had attended his camps – with suggestions that even then-President Robert Mugabe was approached by one of Smyth’s associates.

But from the time of Smyth’s prosecution, the family were given temporary residency permits, which had to be renewed every 30 days.

In 2001, having spent too long out of the country on a trip, Smyth and his wife Anne were refused re-entry, prompting their move to South Africa’s coastal city of Durban and then a few years later to Cape Town, where the couple were living when the Church of England became fully aware in 2013 of the abuses he had committed in the UK.

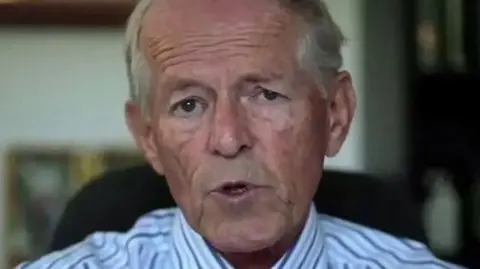

“The Anglican church in Cape The city wherein John Smyth worshipped… has reported that it by no means gained any reviews suggesting he abused or groomed younger crowd,” Thabo Makgoba, the archbishop of Cape Town, said in statement responding to this week’s resignation of Justin Welby as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Smyth was only excommunicated by his local church the year before his death in 2018, after he was named publicly as an abuser in a Channel 4 News report.

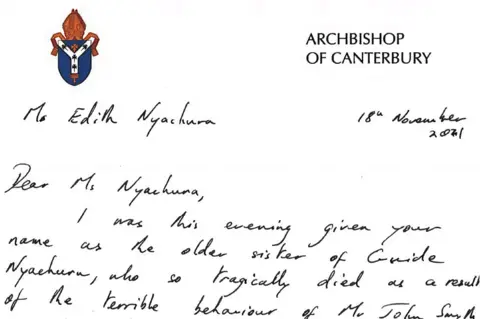

Ms Nyachuru told the BBC it was not until 2021 that she received a written apology from Welby about the death of her brother, in which he admitted that Smyth was responsible and the church had failed her family.

She wrote back describing the apology as “too minute, too overdue” and is now calling for other senior church leaders who failed to intervene to prevent Smyth’s abuse to resign: “I simply suppose crowd of the church, in the event that they see one thing no longer going within the proper direction, if it wishes the police they must proceed to the police.”

Coltart feels it is not just the Church that is to blame, and suggests other institutions in the UK need to face up to their failure to warn people in Zimbabwe.

He commended the Church of England’s recent Makin report, saying it “left deny stone unturned”. The report estimates that around “85 boys and younger males have been bodily abused in African international locations, together with Zimbabwe”.

Coltart urged the Church to reach out to them.

“I feel perhaps there are nonetheless sufferers in Zimbabwe, in all probability in South Africa, who’re affected by PTSD and I feel the Anglican church has a accountability to spot the ones people and to provide them with the clinical aid that they may require,” he said.

Mr Leanders says many of friends are still “so traumatised through the beatings they don’t seem to be even ready to speak about it”.

“Smyth was once safe in England and he was once safe in Zimbabwe. The security went on for goodbye it robbed sufferers the prospect to confront Smyth as adults.”

Alternative reporting from the BBC’s Gabriela Pomeroy.

BBC Motion Layout: You probably have been suffering from problems on this tale, in finding out what backup is to be had right here.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Photographs/BBC

Getty Photographs/BBC