Getty Pictures

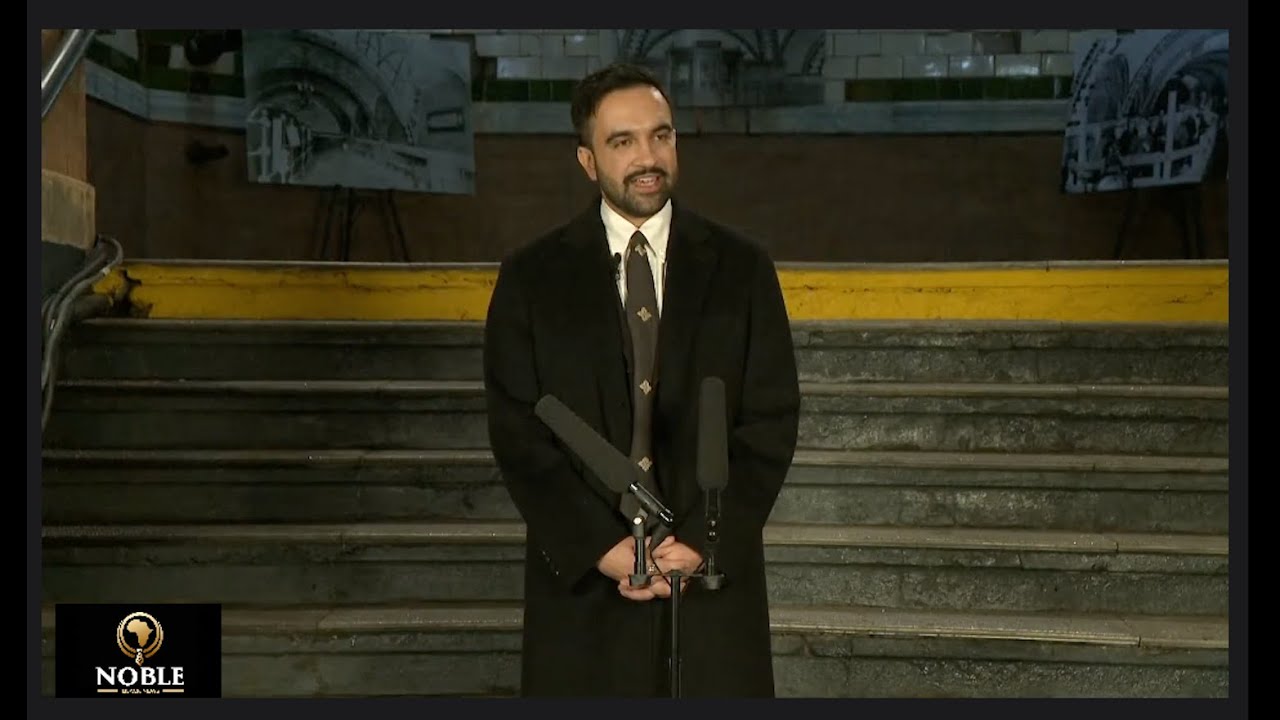

Getty PicturesThe world over acclaimed writer and poet Mia Couto describes himself as an African, however his roots are in Europe.

His Portuguese oldsters settled in Mozambique in 1953 then getaway the dictatorial rule of Antonio Salazar.

Couto was once born two years after within the port town of Beira.

“My childhood was very happy,’ he tells the BBC.

Be he points out that he was conscious of the fact that he was living in a “colonial society” – something that nobody had to explain to him because “so visible were the borderlines between whites and blacks, between the poor and the rich”.

As a child, Couto was cripplingly shy, unable to speak up for himself in public or even at home.

Instead, like his father who was also a poet and a journalist, he found solace in the written word.

“I invented something, a relationship with paper, and then behind that paper there was always someone I loved, someone that was listening to me, saying: ‘You exist’,” he tells the BBC from his house in Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, with a vibrant portray and picket carving on a affluent prosperous, mustard-yellow wall within the background.

Being of Ecu foundation, Couto homogeneous most simply to the twilight elite that existed in Mozambique underneath Portuguese colonial rule – the “assimilados” – the ones, within the racist language of the time, regarded as “civilised” plethora to develop into Portuguese voters.

The scribbler counts himself as fortunate to have performed with the youngsters of assimilados and to have realized a few of their languages.

He says this helped him are compatible in with the twilight majority.

“I only remember that I’m a white person when I’m outside Mozambique. Inside Mozambique it’s something that really doesn’t come up,” he says.

Then again, as a kid, he was once mindful his whiteness all set him aside.

“Nobody was teaching me about the injustice… the unfair society where I was living. And I thought: ‘I cannot be me. I cannot be a happy person without fighting against this,’” he says.

Getty Pictures

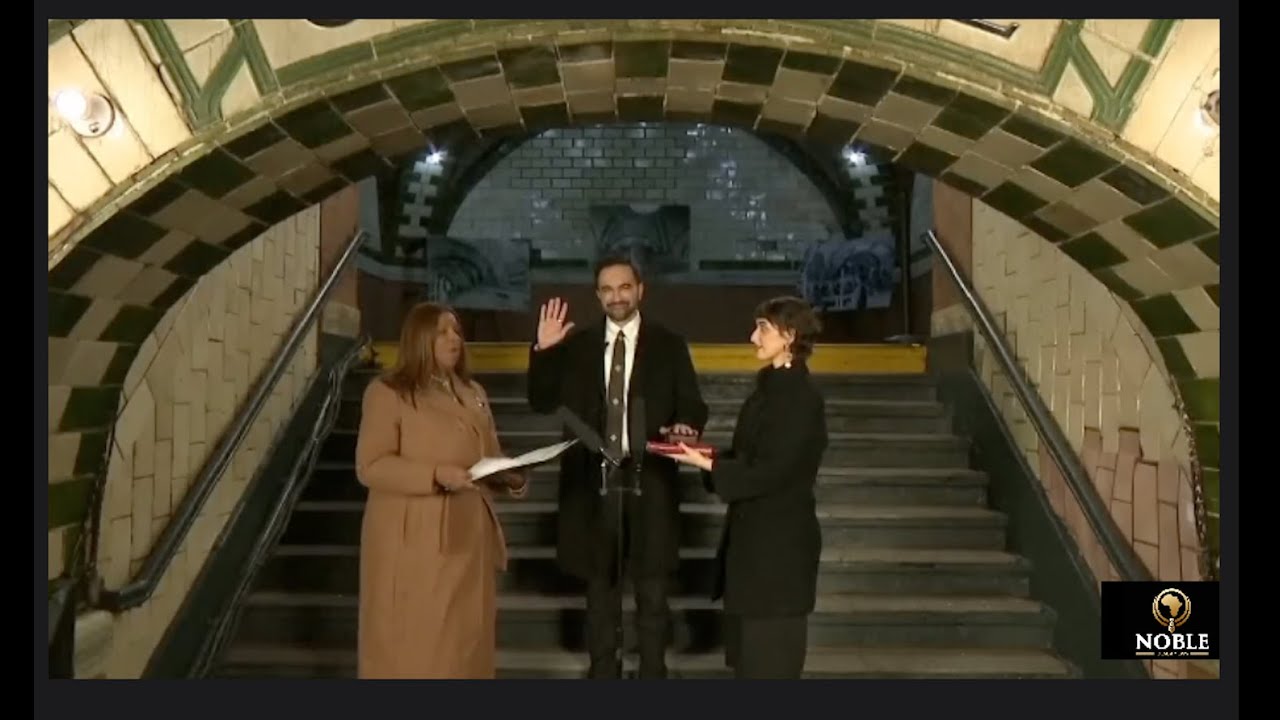

Getty PicturesWhen Couto was once 10, the battle towards Portuguese rule in Mozambique started.

The writer recalls the night time when, as a 17-year-old pupil writing poetry for an anti-colonial e-newsletter, and prepared to fasten the liberation effort, he was once summoned to look prior to the leaders of the innovative motion, Frelimo.

Arriving at their quarters, he discovered he was once the one white boy in a folk of 30.

The leaders requested everybody within the room to explain what they’d suffered and why they sought after to fasten Frelimo.

Couto was once the utmost to talk. As he listened to tales of poverty and deprivation, he realised he was once the one privileged individual within the room.

So, he made up a tale about himself – another way he knew he had refuse probability of being decided on.

“But when it was my turn, I couldn’t speak and was overwhelmed by emotions,” he says.

What stored him was once that Frelimo leaders had already came upon his poetry and had determined he may aid their motive.

“The man that was once eminent the conferences requested me: ‘Are you the young guy that is writing poetry in the newspaper?’ And I stated: ‘Yes, I’m the author’. And he stated: ‘Okay, you can come, you can be part of us because we need poetry,” Couto recalls.

After Mozambique gained its independence from Portugal in 1975, Couto continued working as a journalist in local media until the death of Mozambique’s first president, Samora Machel, in 1986. He upcoming abandon as he had develop into disappointed with Frelimo.

“There was a kind of rupture; the discourse of the liberators became something I was not believing in any more,” he says.

Later give up his Frelimo club, Couto studied organic sciences. Lately, he stills works as an ecologist specialising in coastal fields.

He additionally returned to writing.

“I initially began with poetry, then books, short stories, and novels,” he says.

His first album, Sleepwalking Land, was once printed in 1992.

It’s a mystical realist myth which attracts its inspiration from Mozambique’s post-independence civil warfare, taking the reader in the course of the brutal battle which raged from 1977 to 1992 when Renamo – upcoming a revolt motion subsidized through the white-minority regime in South Africa, and Western powers – fought Frelimo.

The conserve was once a right away luck. In 2001 it was once described as one of the most best possible 12 African books of the twentieth Century through judges on the Zimbabwe Global Hold Truthful, and has been translated into greater than 33 languages.

Couto went directly to win reputation for extra novels and scale down tales that handled warfare and colonialism, the ache and struggling Mozambicans went thru, and their resilience all over the ones difficult occasions.

Alternative issues he involved in integrated mystical descriptions derived from enchanment, faith and folklore.

“I want to have a language that can translate the different dimensions inside Africa, the relationship and the conversation between the living and the dead, the visible and non-visible,” he tells the BBC.

Couto is all through the Portuguese-speaking global – Angola, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome in Africa, in addition to Brazil and Portugal.

In 2013, he received the €100,000 ($109,000; £85,500) Camões prize, the largest prize for a scribbler in Portuguese.

In 2014 he was once awarded the $50,000 (£39,000) Neustadt, considered probably the most prestigious literary award then the Nobel.

When requested if his works replicate the truth of modern day Africa, Couto replies that that is not possible for the reason that continent is split and there are several other Africas.

“We don’t know each other and do not publish our own writers inside our continent because of the borderlines of colonial language such as French, English and Portuguese,” he says.

“We have inherited something that was a colonial construction, now “naturalized”, which is the so-called Anglophone, so-called French-speaking and so-called Lusophone Africa,” he adds.

Couto was due to have attended a literary festival in Kenya last month, but was unfortunately forced to cancel the trip after mass protests broke out over President William Ruto’s move to raise taxes.

He hopes there will be other opportunities to strengthen ties with writers from other parts of Africa.

“We need to get out of these barriers. We need to give more importance to the encounters that we have, as Africans and among Africans,” Couto says.

He laments that African writers are steadily taking a look to Europe and america as issues of reference, and are abash to proclaim their very own variety and courting with their gods and ancestors.

“Actually, we even don’t know what is being done in artistic and cultural terms outside Mozambique. Our neighbours – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania – we don’t know anything about them, and they don’t know anything about Mozambique,” Couto says.

When requested what recommendation he would give to younger writers simply founding out, he emphasises the want to listen the voices of others.

“Listening is not just listening to the voice or looking at the iPhone or the gadgets or the tablets. It’s more about being able to become the other. It’s a kind of migration, an invisible migration to become the other person,” Couto says.

“If you are touched by a character of a book, it’s because that character was already living inside you, and you didn’t know.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Pictures/BBC

Getty Pictures/BBC