Getty Photographs

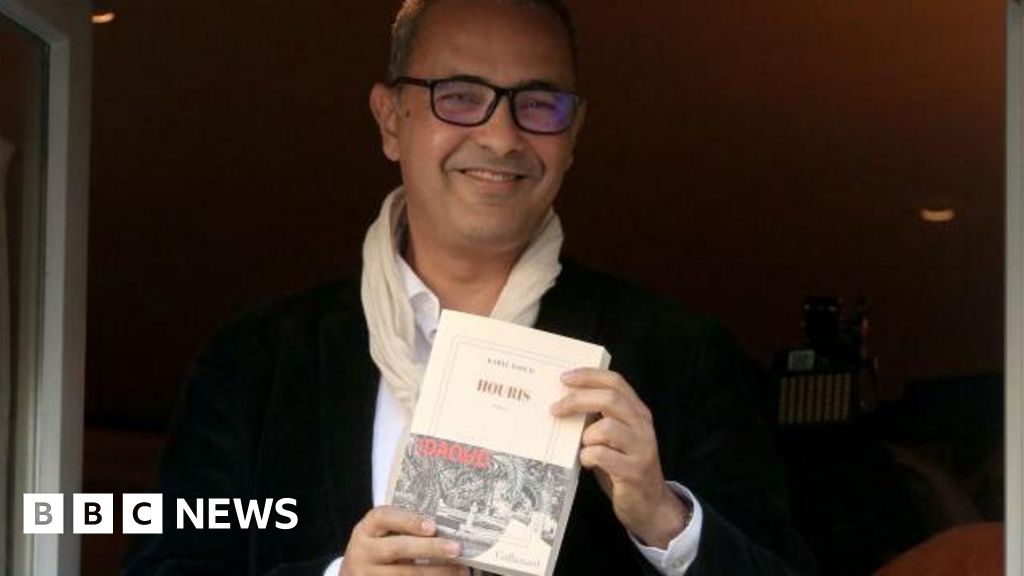

Getty PhotographsFor the primary week, an Algerian creator has gained France’s manage literary award, the Goncourt, with a searing account of his nation’s Nineties civil warfare.

Kamel Daoud’s booklet Houris tells of Algeria’s blood-soaked “dark decade”, by which as much as 200,000 family are estimated to had been killed in massacres blamed on Islamists or the military.

The heroine Fajr (Break of day in Arabic) has survived having her throat short by means of Islamist warring parties – she has a smile-like scar on her neck and desires a talking tube to be in contact – and tells her tale to the child lady she carries inside of her.

Written in French, the retain “gives voice to the suffering of a dark period in Algeria, particularly the suffering of women,” the Goncourt committee mentioned.

“It shows how literature… can trace another path for memory, next to the historical account.”

The irony is that few in Algeria are more likely to learn it. The retain has refuse Algerian writer; the French writer Gallimard has been excluded from the Algiers Retain Honest, and information of Daoud’s Goncourt good fortune has – a date on – nonetheless no longer been reported within the Algerian media.

Worse, Daoud – who now lives in Paris – may even face felony fees for talking of the civil warfare.

A 2005 “reconciliation” legislation makes it a criminal offense punishable by means of prison to “instrumentalise the wounds of the national tragedy”.

In step with Daoud, the impact is to form the civil warfare – which traumatised all the nation – a non-subject.

“My 14 year-old daughter did not believe me when I told her about what had happened, because the war is not taught in schools,” Daoud advised Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut out some of the worst scenes I wrote. Not because they were untrue, but because people would not believe me.”

Daoud, 54, had first-hand enjoy of the massacres as a result of he used to be a journalist on the week operating for the Quotidien d’Oran newspaper. In interviews he has described the ghastly regimen of counting corpses, next optic his rely altered – up or indisposed – by means of the government, relying at the message they sought after to be given.

“You develop a routine,” he mentioned. “Come back, write your piece, then get drunk.”

Getty Photographs

Getty PhotographsHe labored as a columnist for a few years, however progressively fell foul of the Algerian executive on account of his refusal to toe the sequence.

He’s strongly essential of what he sees because the reliable “instrumentalisation” of the 1954-1962 warfare of self rule in opposition to France; and of what he sees as the continued subjugation of ladies in Algerian community.

“In a way the Islamists lost the civil war militarily, but they won politically,” he mentioned.

“What I hope is that my book will make people think about the price of freedom, especially for women. And in Algeria, that it will encourage people to confront all of our history, not fetishise one part over the rest.”

Daoud has written two earlier novels, certainly one of which – the much-praised Meursault Investigation – used to be a rewriting of Albert Camus’s The Stranger and used to be shortlisted for the Goncourt in 2015.

In 2020 the creator moved to Paris, “exiled by the force of things”, and took French nationality. “All Algerians are Franco-Algerians,” he has mentioned. “Either out of hate or out of love.”

In Algeria he’s a divisive determine. His enemies regard him as a traitor who offered his soul to France, time others recognise him as a literary sharp of whom the rustic must be proud.

In his post-award press convention, Daoud himself mentioned that it used to be handiest by means of coming to France that he used to be in a position to put in writing Houris.

“France gave me the freedom to write. It is a land of refuge for writers,” he mentioned. “To write you need three things. A table, a chair and a country. I have all three.”

Inside Abiy Ahmed’s Bold Plan to Transform Ethiopia Ethiopia is undergoing a once-in-a-generation transformation under the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali. From massive infrastructure projects to political…

Inside Abiy Ahmed’s Bold Plan to Transform Ethiopia Ethiopia is undergoing a once-in-a-generation transformation under the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali. From massive infrastructure projects to political…

Africa’s Greatest Exports: The Hidden Power Behind Global Markets Think you know what powers the world? Think again. From rare minerals and coffee to oil, cocoa, and culture, Africa’s…

Africa’s Greatest Exports: The Hidden Power Behind Global Markets Think you know what powers the world? Think again. From rare minerals and coffee to oil, cocoa, and culture, Africa’s…