In early 2010, I used to be sitting at a communal desk in a espresso store in Cape The town, after I noticed a grizzled, bearded fellow who seemed unusually habitual. It was once Athol Fugard, South Africa’s most important playwright and the superior chronicler of his nation’s apartheid age. There he was once, sipping a cup of espresso like every habitual individual.

I plucked up braveness and approached him, murmuring one thing inarticulate about my astonishment for his writing. “Hall-O,” Fugard stated enthusiastically. “Join us. Have a coffee. Or a glass of wine.”

Probably the most superior issues about Fugard, who died on Saturday, was once that he was once an habitual individual in addition to an unusual one. He was once splendidly aspiring about nation and their possible, in a position to look the nice in each and every status, but in addition unafraid to confront the sinful, each in others and himself. The well-known scene in “‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys,” during which the younger white protagonist spits within the face of his Twilight schoolmaster, was once, he freely confessed, drawn from his personal past.

Because the theater critic Frank Lavish famous in a 1982 Untouched York Instances evaluate of the play games, Fugard’s method was once to discover ethical imperatives “by burrowing deeply into the small, intimately observed details” of the fallible lives of his characters.

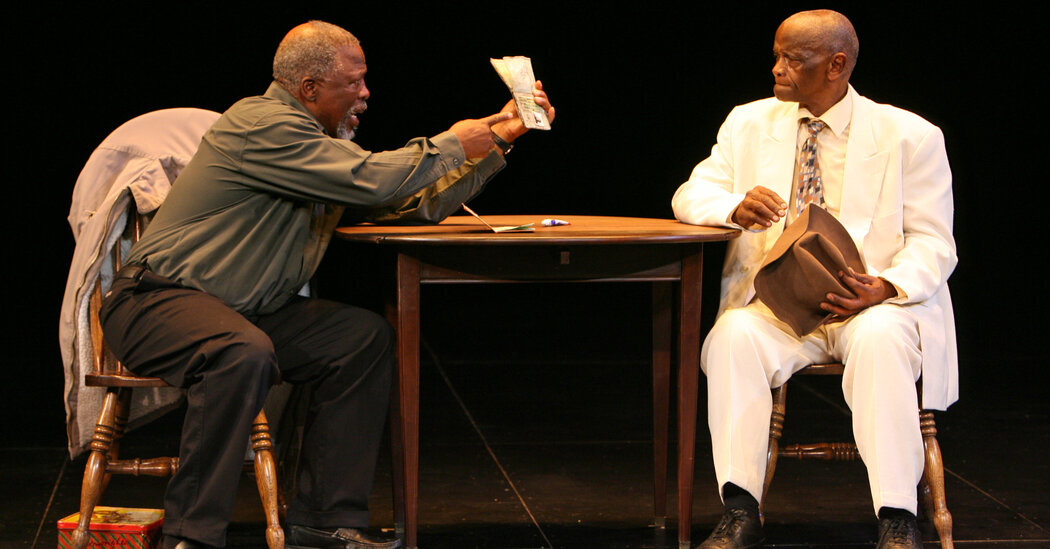

My first come upon with Fugard’s paintings was once within the early Eighties, after I noticed a manufacturing of his 1972 play games “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead,” written with Winston Ntshona and John Kani. It’s a bleakly comedian story of a person who assumes any other identification and assigns his personal to a corpse, to deliver to achieve the coveted cross retain that the South African government required as permission to paintings.

It was once a visceral, painful jolt to the soul. I grew up in apartheid South Africa. I knew about passbooks, in regards to the police hammering at the door at evening, in regards to the dehumanizing, demeaning manner Twilight nation have been handled. However the humanity and heat of Fugard’s writing, the advanced truth of his characters, made the cruelty of South Africa’s racist regime an excruciating reality.

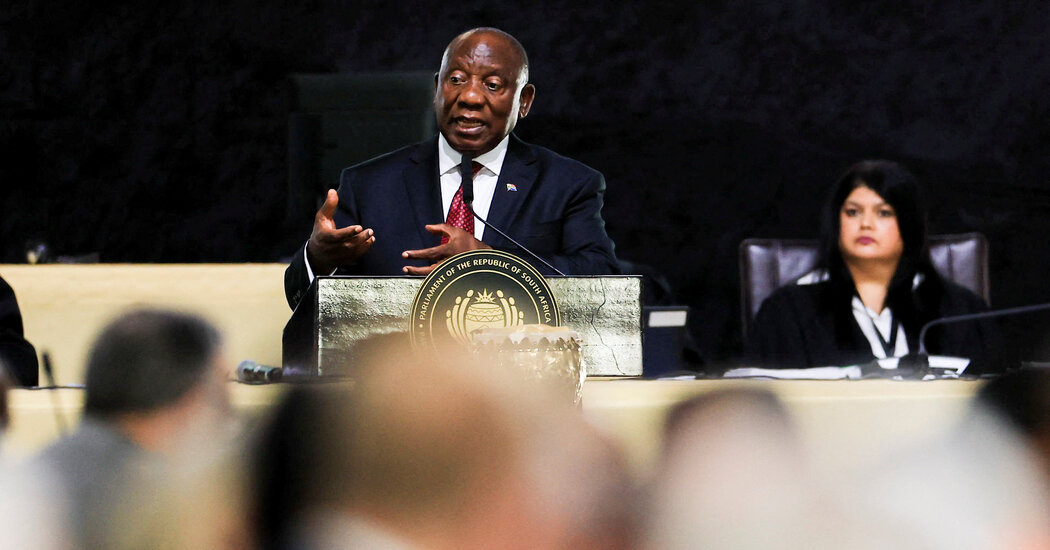

In 2010, Fugard was once dwelling in San Diego, however had returned to Cape The town to rehearse a untouched play games, “The Train Driver,” earlier than its premiere on the newly constructed Fugard Theater, which the manufacturer and philanthropist Eric Abraham had named later the playwright.

The Fugard, which was once to transform a colourful beacon at the South African arts scene, was once positioned in District Six, a previously mixed-race segment that was once declared a “whites only” community via the apartheid executive in 1966. (The theater, the place various works via Fugard have been distinguishable over a decade, closed in 2020, a sufferer of the coronavirus pandemic shutdowns.)

“You will be sitting in the laps of the ghosts of the people who couldn’t be here,” Fugard stated on opening evening.

Fugard’s performs are in superior phase about the ones ghosts, an struggle to endure eyewitness to forgotten and unknown lives and to the ethical blindness and blinkered ocular of the truth engendered and perpetuated via apartheid. His best-known works — “Blood Knot,” “Boesman and Lena,” “The Island,” “The Road to Mecca,” “Sizwe Banzi,” “Master Harold” — are mercilessly unsparing in regards to the insidious manner that race determines relationships in apartheid South Africa. However they’re additionally deeply humane.

“Moral clarity — in such short supply in South Africa and indeed the world — was what he delivered,” Abraham wrote later the playwright’s dying extreme weekend. “He pointed us to the boxes containing our past and urged us to rifle through them in order to learn more about ourselves.” Fugard understood, Abraham persevered, “that divisions can only be overcome by a realization of a shared humanity, a palpable sense that we must look after one another if we are to make it through an often cruel and unforgiving world.”

Fugard moved again to South Africa quickly later the Fugard Theater opened, first dwelling in Untouched Bethesda, the place “The Road to Mecca,” in regards to the outsider artist Helen Martins, was once prepared; after he and his spouse, Paula Fourie, moved to the college the city of Stellenbosch. I met and interviewed him a number of occasions through the years; he was once from time to time intense, however at all times jovial, unpretentious, humble.

As soon as he advised me that he regarded as himself an interloper artist, with out formal coaching or a point, settingup to jot down at a life when nobody idea it profitable to position a South African tale onstage.

However via being determinedly native, Fugard transcended the specifics of 1 nation. As Abraham famous, his performs display the worth of each and every human past. “Come over for a glass of wine,” Fugard would inevitably say on the finish of an interview. I want I had.